Housing Action Groups in Europe, Friday, 17th April 2015

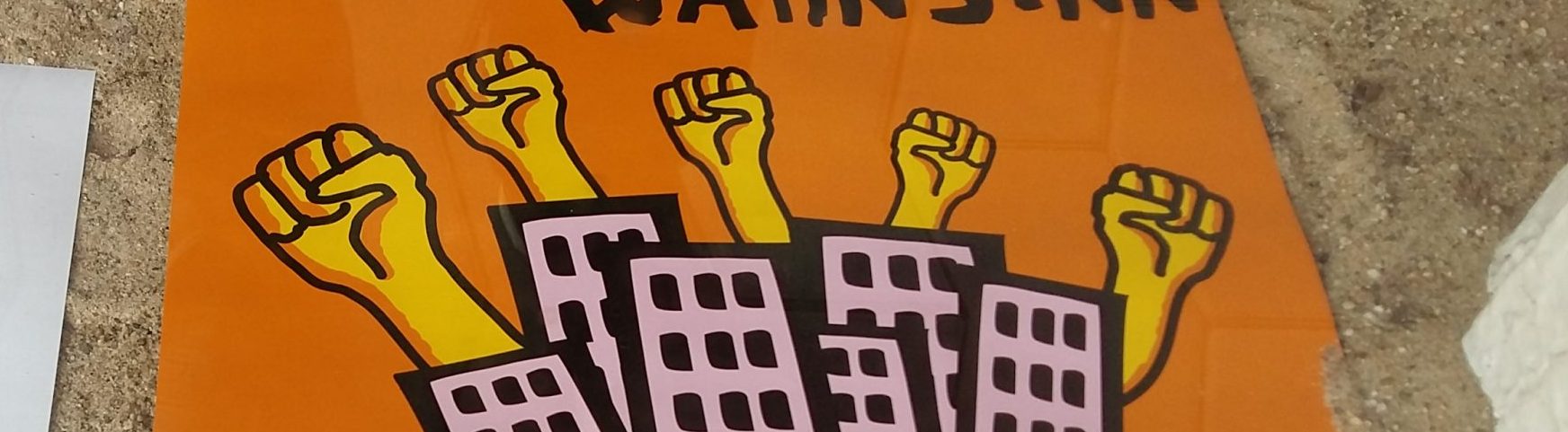

The undersigning organisations, united in the struggle for the right to housing and to the city, strongly support the protests against the planned free trade agreement TTIP (“Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership” between EU and USA) and the already negotiated CETA (Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement). All over Europe protests will take place at 18th April.

Environmental groups, consumer associations, trade unions and other civil society organizations since years have been warning that the free trade regulations discussed as TTIP will undermine environmental standards for agriculture, health standards for food and labor standards for services. Because TTIP is negotiated in strict secrecy and because of the plan to introduce extra-static arbitral tribunals for investor protection (“investor-state dispute settlement”) many critics fear that the agreement will dispend national sovereignty and democracy. Anti TTIP-campaigners also expect negative consequences for the protection against fracking, for public education, municipal services and for regulation of financial products. We fear that TTIP will also have disastrous consequences on urban development, real estate, housing and land markets.

Because TTIP is discussed behind closed doors we cannot know the details and concrete consequences of TTIP on housing and cities so far. We do not know if these aspects are an issue i the negotiations at all. But we did not notice any signal from the negotiating parties that an exclusion of real estate, public/social housing or a regulation of financial investments will be discussed, and such an exclusion also would be difficult to implement. Thus, we have to fear the worst. TTIP and CETA can have much impact on housing and cities in our countries.

As far as we can figure out from scarce and confusing information TTIP has four targets: (1) reduction of non-tariff trade barriers, (2) protection of transnational investors, (3) harmonization of industrial standards, (4) introduction of commercial arbitral tribunals. Each of these targets can affect housing, land and cities in various ways.

(1) The planned reduction of non-tariff trade barriers may disallow existing or demanded national restrictions of transnational capital mobility and transactions, including regulations of trade with houses and land. So far, some countries in Europe still limit the right of foreigners to own (agricultural) land and houses. Others exclude parts of the land and housing from markets, i.e. through systems of social or public housing. Everywhere national property registration regulations could be interpreted as trade barriers. In the TTIP negotiations such market restrictions could be questioned. Consequently, more property could become targets for transnational financial investors. National or European regulations on mortgage systems can be seen as a trade barrier for the financial markets too. Because of stricter regulations mortgaged homeowners in the U.S: could be the first victims. All this can lead to an even faster globalization of housing finance. Besides the transnational concentration of capital the consequence will be an increased risk of new real estate and financial bubbles.

(2) The discussed protection of transnational investor rights can directly affect national or local policies towards housing stocks, which are owned by financial funds or by joint stock companies with international shareholders and subsidiaries. This sector includes the wide-spread private-public partnerships in social housing and public infrastructure, even joint-ventures which have been pushed by the European Commission, i.e. in Italy. Any limitation of the commercial exploitation of the property – i.e. through improved rights for tenants, new urban planning obligations or taxation of transactions – can be interpreted as a violation of property rights and of investor security.

This is especially true if governments want to introduce new regulations. The introduction of private insolvency regulations or the requisition of empty flats for social housing, which are realistic expectations in possible progressive governments after elections in Spain, could be attacked by funds like Blackstone or Goldman Sachs, which have already invaded the domestic housing and mortgage market. As a consequence even countries which already have private insolvency regulations (many) or allow requisitions (i.e. Italy and France) could be under pressure. Necessary improvements of the security of tenure could be attacked by U.S. shareholders as well. The introduction even of a little stricter rent regulation, as just happened in Germany, could be understood as a threat of the investor security if US or Canadian shareholders in German housig compenies, like Blackrock or Sun Life, think that the fair value of the housing companies is affected.

(3) The harmonization of industrial standards potentially affects the whole range of consumer rights and may lead to a weakening of standards for construction and building material, for facility services and architects, for financial products and mortgage contracts. Regarding construction products it can become a threat on ecological standards (i.e limitations of tropical woods), health standards (i.e use of unhealthy substances) and social production standards (i.e. working conditions). Because public authorities at the same time will be forced to take the cheapest offer from company, global competition will push the already existing race to the bottom.

(4) The planned arbitral tribunals (“investor-state dispute settlement”) will judge violations of the free trade agreements without being bound through national laws, constitutions or international human rights. In many countries they will simply be extra-constitutional. According to the constitution of many European countries, property leads to social obligations. That is not the case in free trade agreements. In this context it is important to note, that already the risk of a high claim for damages by big companies will have strong influence on legislation. (“chilling effect”) Governments will not dare to improve rent control or limit building permission on a territory if they have to fear a claim of billions of dollars because of the financial losses of investors.

We don’t know, if any exclusion of housing and real estate from TTIP will be discussed in the secret negotiations. However, it is hardly possible to reduce TTIP on specific branches or investor seats and exclude such central sectors as real estate and its finance, if free trade with services and material is the aim. If there is a free trade with agricultural or extraction products construction material cannot be excluded from that free trade. In all branches companies can have transnational shareholders, specific subsidiaries or financial investors in funds and bonds, who can claim to be affected by any national regulation. Transnational investors also can easily change the composition of their trust and holdings if that is necessary to avoid taxes or regulations on specific branches. I.e. a private equity firm, so far indirectly invested into agricultural land, renewable energy, cinemas and housing could easily construct a multinational company which combines the energy, land and property business and therefor claims transatlantic investors’ interests in all these branches. Banks simply can use existing subsidiaries or set up special vehicles in Europe or the U.S. to attack national regulations at the arbitral tribunals. Even smaller landlords or other investors could build joint ventures in the U.S. or Europe in order to be able to claim transatlantic investor rights. For sure, national lobbies of the real estate sector will think about such solutions if that gives them power in national disputes on housing policies.

This all will have deep effects on local urban development and master planning. A transatlantic firm which has bought land in an development area could claim a violation of investment security if the city council later decides to reduce the commercial building density, increase the portion of social housing construction or green spaces, or stop the project. This will give much more power to private developers in the master planning of large urban development projects like water fronts, factory outlet centers, or urban cleansing of traditional neighborhoods.

Local democracy will be lost. This is even true for local housing policies and public building. Local plebiscites for alternative urban plans or better social housing, as currently on the way in Berlin, could be confronted with the option that transatlantic commercial courts will stop the implementation. Municipal building standards – like the obligation to use environment friendly products or to pay minimum wages to foreign construction workers – would be under pressure as well.

Finally, TTIP and CETA will heavily influence policies at the European Union level. In the construction, facility and financial industries many consumer and product standards could be under pressure if they do not harmonize with those in the U.S. Demands for stricter regulations of hedge and private equity funds, of stricter taxation on cross-border transactions, for binding housing rights standards and for social housing obligations would have to face another strong challenge. Then the attacks of the European Commission against public/social housing in many countries had only been a foreplay of what can happen with TTIP. The handing over of Europe to the global financial markets would be completed.

Thus, as organizations of local tenants and inhabitants we have to fear that the planned agreements will cause another heavy push towards privatisations and investor-control in our cities and villages. TTIP can trigger another tsunami of dispossession of people from their land, housing, social infrastructure and democratic territorial management, in Europe, Northern America and beyond. Instead of learning the lessons from the 2007/08 crashes and it’s aftermaths it will continue the globally destructive path of neo-liberalisation, which gets backed by so many governments and agencies, including – in the field of housing and cities – the preparation of the UN-conference Habitat III.

We must stop them.

We need strong alliances between European and North American social movements, including organizations of inhabitants and tenants, demanding governments not to approve the TTIP.